Binary Search Tree

Trees are another way to structure data. They work differently that arrays so we won't be looking at the exact same thing but they have their own uses. Arrays can have arbitrary data in arbitrary order. An array of [1, 5, 2, 7, 3] is totally fine: it doesn't have to be in a sorted order. The kind of trees we're going to be looking at today are all ordered by value, so whenever you insert a new value, it will be inserted in a sorted fashion e.g. if we add 5 to [1, 4, 6, 7] it must be inserted between the 4 and the 6.

There are many varieties of tree data structures. We'll be looking at two of them today, binary search trees and AVL trees, but there are so many more. They're used everywhere due to their fast access patterns, even across enormous data sets.

At its core, a tree is very similar to a LinkedList. You have nodes. Those nodes have values and pointers to other nodes. Unlike a LinkedList which only has one next pointer (or maybe a next and previous) trees can have many pointers. We're going to be looking at two types of trees today that have just two children nodes: binary search trees and AVL trees (which are a special type of binary search tree).

The first one we'll be looking at is a binary search tree (from here-on-out I'll abbreviate binary search trees as BSTs.) The binary part means there are at most two children nodes per node and the search part means that it's particularly well suited for "search" scenarios e.g. you need to be able to rapidly access data in it, even if it means slower inserts and deletes.

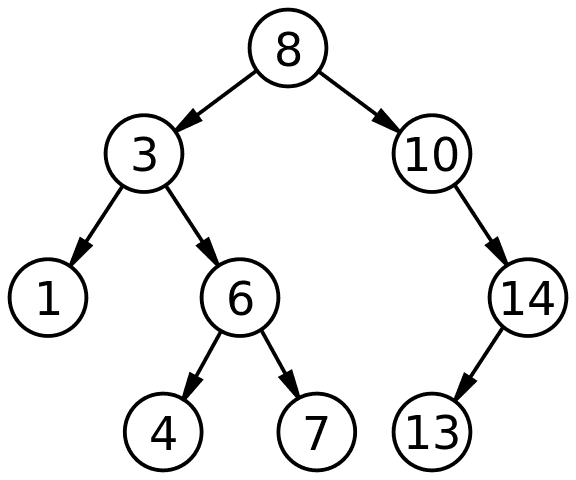

So we have one node that is the root. That node can have a left child and a right child. It can have both, one, or neither. Every node has a value. Both children are nodes just like the root: they can 0-2 children as well and will always have a value (there are no nodes without values.) Every value in a node's left tree is smaller than its value and every node in its right tree is larger than its value. Values that are equal can go either way, just be consistent. I tend to put equal values on the left.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

If the any of the above rules are violated, then your tree isn't a binary search tree. All of them use be followed 100% of the time. Because of this you can make assumptions about it which it makes really fast to use in certain scenarios. We'll talk about that in a bit.

Look Ups

Let's talk about about how to do a look up. Say you have the above tree and you want to find 4.

-> .find is called with 4

-> start with root 8, 4 is smaller so go left

-> node 3, 4 is larger, go right

-> node 6, 4 is smaller, go left

-> node 4, found resultThis is the whole algorithm for look ups. Go left or right depending if it's smaller or bigger (respectively) and then you'll find it. What's the Big O here? In this case, we're not hopefully not looking at every item in the tree, just some small sampling of them. The average case here would be O(log n). The best case is that someone asks for the root which be O(1). The worst case if that if you have a poorly made BST where every child is on the left (or right) and you have to look at every item in the array to find it. That would be O(n).

Add

What if we want to add an element to the array? The good news is you just reuse the find method we defined above and when you find where the element should be, you just stick in a new item! Let's give it a shot.

Current Tree:

10

/ \

5 15

/ \ /

3 8 12

-> .add is called with 7

-> start at root (10)

-> lesser than 10, go left to 5

-> greater than 5, go right to 8

-> lesser than 8, go left

-> no element at left, create new node

and make it the left subtree of 8

10

/ \

5 15

/ \ /

3 8 12

/

7Delete

Pretty similar to an add but a few additional steps. Let's take the tree

10

/ \

5 15

/ \ / \

3 8 12 17

/

6

\

7Let's say we want to delete 5. Obviously a node still has to exist there, and remember all nodes have values. So how do we delete 5 without fracturing all the assumptions of the BST? There are two ways: replace 5 with the smallest child in the right child's subtree or the greatest child in the left subtree. Let's do the former. What is the greatest child in the left subtree? Well, you just follow right children in the left subtree until you hit the last one. In this case, it's just 6, only one hop. But if 5.5 was there, you'd hop one more.

Okay, so we found the least child in the right subtree. By definition, this node will not have a left child. Otherwise what you found wouldn't be the least one in this subtree. We're going to do two things: take its value and replace the value we're trying to delete (in this case 5) and then move 6's right child to node we're over writing's left child. Let's write that step-by-step.

-> .delete called on 5

-> call .find on 5

-> start with root, 10. 5 is less, go left

-> found 5

-> .findLeastRightChild with 5

-> go right on 5, land on 8

-> go left as far as we can. only one hop, 6

-> replace the node that 5's value with 6

(the new 6 / old 5 node will be represented as 6')

10

/ \

6' 15

/ \ / \

3 8 12 17

/

6

\

7

-> set 8 left child to be 6 right child

10

/ \

6' 15

/ \ / \

3 8 12 17

/

7This is the most complicated scenario. Let's glance at the other two possibilities.

10

/ \

5 15

-> delete 15

-> it has no children (leaf node), set its parent right child to null

10

/

5In this case you just wipe out the whole node when the node to delete is a leaf node.

Okay, one more case.

10

/ \

5 15

/

12

/ \

11 14

-> delete 15

-> 15 has no right child but does have a left child

-> set 10 right child to be 15 left child

10

/ \

5 12

/ \

11 14When one of the children is null, you can just move its entire child to be the new child.

The Big O of this would be still be O(log n). Despite it being more steps we don't normally need to look at every item in the tree.

Worst Case BSTs

Let's look at the worst case BST: if you have a sorted list of numbers and just added them in order.

1

\

2

\

3

\

4

\

5Unfortunately a BST has no way to deal with this. This is why you'll never use BSTs directly yourself. There are variations of BST that are built to deal with these. We're going to look at one of them, the AVL tree, in the next section.

Why Use a Tree

We went through a lot of trouble to learn about trees. Why would you ever use one? It's because they're very searchable. You're doing a bunch of work up front to make them easy to search later.

One really good example that very frequently uses some variety of tree is database indexes. Let's say you have a database of all your orders and customers frequently search for their order by order number. We don't want to comb the whole database to find the one order: that'll be slow and taxing on your database. We also don't want to store the whole database in a tree: sometimes we want multiple indexes and we want to optimize the database so we can write quickly to it which keeping it in a tree would hinder.

So we'll store the whole database in one data structure and then we'll keep a separate tree that we can use an index. When a user searches for their order number, we do a fast find on our tree, it points to where the item is in our database and we get a fast look up on a big database. O(log n) on large datasets is very fast.

Exercises

We're going to work on /specs/bst/bst.test.js. Go give that a shot.